David

Heiller

Mom and I were looking through

some old photos a couple of month ago. They were from the Schnick farm in about

1920. Most showed scenes and people. There were several pictures of women in white

on a picnic on one of the bluffs.

|

| Unfortunately, I only have a photocopied version of this photo.I would love to have an "actual" image, if any one from the area has one that they would be willing to share. |

Then the photographer, probably

Ben Schnick, did a very good thing and turned his camera toward the Mississippi River and took the picture shown here.

It is taken from the bluff just

to the north of Shellhorn Road. You can see the railroad track parallel to it.

What’s amazing to me is how

different the river looks. For one thing the main channel, known as Raft

Channel, hugs the Minnesota shore then jogs to the east around a big spit of

land in front of where Valeree Green now lives.

That whole stretch of river

with all its timber and islands and sloughs is now pretty much an open expanse

of water thanks to Lock and Dam number eight at Genoa, Wisconsin.

That dam and 28 others were

built as part of the Nine-Foot Channel Project. Most were built in the 1930s.

The Genoa dam was built from 1934-1937. When the photo was taken, the Main

Channel was kept at a depth of six feet

as Congress authorized in 1907. This act authorized 2,000 additional wing dams,

dredging, and dams at locks at Keokuk and LeClaire, Iowa.

When the locks and dams were

constructed, the water rose and the lower ends of each pool were inundated. The

beautiful bottomland shown in this photo disappeared. I remember my Uncle Donny

telling me that the Genoa dam took away a good chunk of Heiller farmland, which

is barely visible in the upper right hand part of this photo. He wasn’t real

happy about that. It wasn’t great farmland, being susceptible to flooding, but

it timber and hayfields and pasture.

I bet people like Donny were upset with the project for

recreational and aesthetic reasons too. When I see photos like this, I

want to hop in the canoe and go fish and explore. The river was more like a wilderness then. Imagine the Reno Bottoms extending all the way up and down the river.

That’s what it was

like.

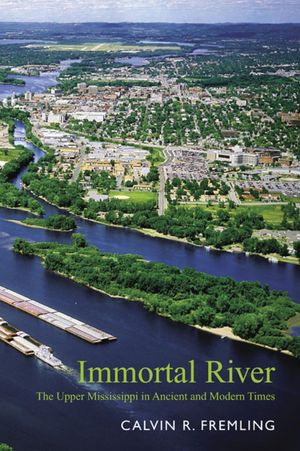

Calvin R. Fremling gives an excellent account of this (and much more)

in his book, Immortal River. “Prior to the inundation

in the 1934-1940 period, the river bottoms were primarily

wooded islands

separated by deep, running sloughs.

Hundreds of small lakes and ponds were scattered through the wooded

bottoms. Bay meadows and small farming operations, mainly haying and grazing occupied some areas on larger islands,” he writes at

the start of a chapter called “The Glory Years.”

Some good

things, beside improved commerce, did come out of the damming of the river, Fremling

says. One thing I like is that it converted ownership from private to public.

“In an era when ‘no trespassing’ signs were becoming increasingly prevalent, it

made the lands available, in perpetuity, for public use,” Fremling notes.

Anyone who uses the Upper Mississippi River National Wildlife and Fish Refuge

can be thankful for that.

The Nine-Foot Channel Project also controlled flooding, and enhanced

the opportunities for recreational boating. It increased more fish-food

organisms and more fish because the river’s surface had increased exposure to

the sun’s energy.

This is just some of the great information in Fremling’s excellent book.

It’s like a Bible of river history, geology, and science. I couldn’t recommend

a book more highly.

But I’ll still reminisce about a river I never knew, one my

great-uncle Ben captured so many years ago. I know, time marches on, progress

is good, people are starving in China, blah blah, blah. But we should remember

that we lost a tremendous resource right in our front yard when the river was

dammed.